He had great faith in human nature.

He had great faith in human nature.

He fully believed that most persons were honest and dutiful and capable of many sorts of work.

He urged emancipation from superstitions and appetites.

His strength and solidity were based on a strong sense of humour and a comprehensive philosophy of life.

He had no strong desire for external possessions, but he possessed his own soul and had no demons.

He had great faith in his own convictions, and while not given to dispute, he was not inclined to conciliate opinion.

He was rich in friends and enjoyed life with them as he went, so that when he lost, a friend by death he did not seem to have any vain regret for neglect to give all he could while they were alive.

Charles Riordon was born on November 28th, 1847, in the Village of Bally Bunion, County Kerry, Ireland, the seventh child of Jeremiah Riordon, who had been a medical offiver in the Navy from 1807 to 1821 serving on ships of the frigate class, including the ‘Bellerophon’ during and after the Napoleonic Wars. The family came to Canada in 1850, lived at Weston Ontario for some seven years, and then moved to Rochester, N.Y., where Charles Riordon received his education.

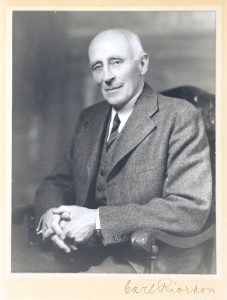

He returned to Canada in 1863, at the age of fifteen, and joined his brother, John Riordon, in building a paper mill at Merritton, Ontario, becoming Manager in the following year at the age of sixteen, and in 1866, at eighteen, he went alone to England and brought back machinery for a new mill. In 1869 he inaugurated the use of groundwood pulp, which was used in place of straw and in 1885 went to Austria and Germany, to study their methods of producing sulphite pulp, bringing back from the latter country two digesters which were floated down the Rhine, and, being too large to go into any cargo boat, were brought to Canada in sailing ships, from which the decks had been removed and replaced. The first sulphite pulp was made in 1887 in Merritton and Cornwall. The Hawkesbury mill was built in 1898, and the Kipawa mill, together with the Town, in 1917-1918. Many timber limits were acquired, and in 1920 the Company gathered together all the properties on the Gatineau, enabling them to be developed as a unit. In 1877 the Toronto Daily Mail was bought, and Mr. Riordon remained its President until its sale in 1927, a period of fifty years, during which time he was a strong supporter of the Conservative Party, and an important factor in the establishment of the ‘National Policy’ under Sir John Macdonald in 1878, and was also an early member of the National Club in Toronto in this connection. The Empire newspaper was bought in 1891, the two forming the ‘Toronto Mail and Empire.’ Mr. Riordon was a man of great courage and creative ability a pioneer in spirit and always did his utmost to assist in the development of Canada. He was instrumental in building two railways, the ‘Temiscouata’ from Riviere de Loup to Edmundston, and the ‘International’ in New Brunswick, also in rebuilding the Niagara Falls Suspension Bridge, of which Company he was for some time the President, and a Director for nearly fifty years. He was throughout his life a great reader and student, especially of philosophy and the humanities, a taste inherited from his grandfather and father who was a well known classical scholar and a Fellow of Trinity College, Dublin, and it was due to his interest in education that he materially assisted in founding ‘Ridley College’ at St. Catherines, Ontario. He has lived in Montreal for the past ten years, having sold his place in St. Catherines, in which he had lived since 1869. In 1887 the family moved to Toronto, only using the St. Catherines house in summer, but returned to it in 1894 and it remained a headquarters until 1921, when it was sold to the City of St. Catherines as a public park. Mr. Riordon was a man of very simple tasted and latterly had lived in seclusion, but he was much loved and respected by all with whom he came in contact, and all through his life he spent a part of his income in helping individual cases of hardship or distress. He was a member of many clubs, including the Toronto and National Clubs in Toronto, the Rideau in Ottawa, and the St. James’ and Mount Royal in Montreal, though he had resigned from some of these of late years. He is survived by one son, Charles Christopher (Carl), and three daughters Mrs. S. B. Pemberton, of Montreal, Mrs. Cromptom, of ‘Broomfield’, Morley, Derby, England, and Lady Goold-Adams, of 10 Cavendish Court, Wignore Street, London, England. He was married in 1873 to Edith Susan, daughter of J.E. Ellis, of Toronto. Mrs. Riordon died nearly two years ago, in May, 1930.

From Napolean to Merritton

From some friends in the industry who were particularly close to the late Mr. Riordon, we have been successful in securing a number of anecdotes which are remembered out of conversations with Mr. Riordon over several years. Mr. Riordon was a very retiring person, and the quaint and almost shy way in which such episodes were recounted, it will be realized by those who knew him, was far removed from any commitment to type. They are, as it were, the small private sketched which am artist would make for the eyes of his intimate friends.

A Link with the historic Past

It is not realized what a great link in terms of time Mr. Charles Riordon’s life constituted with what we regard as “history”?. The following, condensed from casual conversation with Mr. Riordon, tends to show what a period his life covered: ‘My father, who was educated at the London Hospital and Trinity College, Dublin was posted in 1807 to the Navy, then engaged with the war with France in various parts of the world, and was sent to Jamaica in 1821 as chief medical officer. At that time the conditions surrounding surgery were not very far advanced, and deaths from fever were fairly common. Indeed my father was stricken with some sort of fever peculiar to the tropics and never really recovered. He used to suffer the most violent headaches even after twenty years. He was one who encouraged a practice then growing up of giving seamen the juices of fruits, such as lime, as an antidote to scurvy. It is interesting to see how without knowing the reasons which modern science has brought forward, in the discovery of the so-called vitamins, the British Navy was following a sound practice. After the Battle of Waterloo, when Napoleon was confined in the Bellerephon at Plymouth my father on the flag ship of the British Admiral used to see Napoleon walking the decks of his vessel, with British officers and with, occasionally, his French military confidants. The greatest care was of course taken against any untoward incident. When it was decided to send Napoleon to St. Helena, my father, as the senior surgeon, was tendered the post of surgeon in the British headquarters on the island of exile. As it happened, my father was then involved in a court martial…a dispute with some Admiral in the Navu who insisted upon the appearance of vertain junior officer who had been sent to the hospital by my father’s orders. The court martial was a rather bitter affair; my father won his point against the Admiral but it prevented him going to St. Helena with Napoleon. His assistant O’Meara was then chosen for the task, and his memoirs of Napolean are preserved in the book ‘My Years of Exile with Napoleon.’ In 1849 the family came to Canada. My father later left the Navy about 1827 and married about 1833 and settled in the west of Ireland. When he brought his family to Canada in 1850, we settled in the village of Weston, not far from Toronto, where he built up a large pratice and was well known throughout that part of the country. After my father;s death in 1862, said Mr. Riordon, my brother John was at first engaged in the wrapping paper business in Brantford in 1857. Later, when John decided to open a mill at Merritton, Ontario, he worked upon it for a time and then sent for me, stating that he did not want to carry it on but wanted me to take charge. I was then only fifteen, but the men in the mill were very friendly and the first thing that I did was to get them together and acknowledge that although I was very young my brother had asked me to take charge and if we worked together I felt sure we would make a success. They all agreed to help me, and we did make very good progress. At that time newsprint was made from rags and we had to buy our stocks of rags from all over the country-side and we sent out little advertisements asking the people to save their rags so as to make paper. Later, the use of straw for paper came in.

Some of Mr. Riordon’s Recollections

Among the farmers in the County of Lincolm our mill had a very enhoyable reputation because the price which we were able to secure for our newsprint, particularly in the United Stated at the close of the Civil War made it possible for us to pay a very good price for straw. Some of my happiest recollections are in my relations with those farmers.

Explanation Wins Cooperation

After my trip to Austria and Germany, as a result of which I brought to Merritton the equipment and the knowledge which would establish the manufacture of sulphite, we had naturally a number of defects in getting the mill into successful operation, but some peculiar troubles developed later which were most mysterious. The mill was losing money and the loss was later attributable to lack of output. For some weeks I was not able to account for the fact that although we put in certain quantities of wood we got a quantity of pulp far below what might have been expected. Questioning of the men did not seem to give any good result, so I determined to investigate for myself. I went quietly to the mill when the men were having their midnight lunch and looked around as well as I could but could not find anything wrong. However, on my third visit of this kind I decided to go down into the pits. It was a little risky because I had to go without any light, but I went through the layer of pulp in the bottom of the pits and felt around until I got to the emergency plug and discovered that it had been removed and the pulp was simply being let out into the canal. I came back to the foreman and asked hum why he did this, and he said that he did not want to be troubled taking care of that-that he wanted a little more time for his supper and to take a rest. He was a decent sort of a fellow and when I told him how much it meant to the Company he felt very badly and we never had any further trouble on that account.

Worked Seventy-two Hours

Sometimes, however, we had to work very long hours. On one occasion when there was a break in the water wheel we worked steadily for three days. The men had some rest but I did not take any myself until on the night of the third day when I went over to the office and sat on the book-keeper’s stool and put my head on the tall desk. Before I realized it I was asleep and when I woke up in about twenty minutes I went over to the mill only to find that all the men had gone home. I then went around to their houses and tried to get them out but all of them reused except two men and they came and we worked through until the morning when the other men came on again and we finally completed the job. I was much annoyed with the men who would not come out, but then, poor fellows, one could not very well blame them, Some of them had taken some whiskey, I am afraid, and they id not get around to the mull until much later in the day.

Liquor in the Boiler Room

Once we had a man who was prone to take too much liquor and he nearly brought about a disaster. When he was partly drunk he got the idea that I had complained that the steam pressure was not high enough, so he put the weight away up on the safety valve and then went at his duty as he conceived it which consisted of alternately stoking the boiler and stoking himself with whiskey. I happened to come around and hearing the steam rush from imperfections in the tubing which had been discovered by the unusual pressure, and found the man asleep in his chair in the boiler room. I verily believe that the steam was going through tiny holes in the boiler but as there was no time to lose I got up on the top of the boiler and eased the safety valve gradually until the pressure was down. The needle on the indicator was over to the extreme limit of pressure and from examinations which were made afterwards it was clear that the boiler might have exploded any moment, so it was lucky that we caught on in time because it would otherwise probably have wrecked the entire mill and would have damaged property outside it. I discharged that man as we could not trust him.

Bright Idea Started Fire

There was another occasion on which the foolishness of one of the men nearly lost us the mill. Originally the place had been occupied as a woolen mill and the roof had become imperfect so that when we took it over we put a new roof over the old one and at the ridge it was about a foot and a half or so above the old ridge. Therefore when the men wanted to make a hole through the ridge from the inside of the mill to the open air they found that their augur was not long enough and they could not locate the hole from the outside which they had begun from the inside. One bright man therefore conceived the idea of heating a 6-foot poker red hot in the boiler house and pushing it up from the inside through the two ridges. The very dry wood in the ridge couple with the draft that was created when they put the poker through at once started a fire which we had very great difficulty in extinguishing because it spread very rapidly between the two roofs. In speaking of foolish people, I should not neglect to include myself, for I was at least so designated by my brother. At the time that we were building the mill at Merritton at Lock 17 I was not content with the aquare, uncompromising appearance of the walls, and at one corner I desired to build a little tower, MY brother and I had a number of arguments about it; I finally gained my point but the tower was promptly dubbed by my brother ‘Charlie’s Folly’ However, whatever one might say of the little tower, I think it is true that the mill was well built, for through all the years that I had to do with it there was not a single crack in the foundations. The difficulties of operation were far greater in those days than today, particularly in the matter of replacement of broken parts. Once when the large cog wheel on the waterwheel line broke, I was told by the man who had cast it that it would take at least three weeks to make another. Such a condition was, of course, impossible for us if we were not to lose a good deal of money, so I determined to mend the thing as well as I could myself. I bored holes in the sides of the wheel, and in the part which had broken out and bound it together with steel straps. The work took two days working day and night and every one of the men said that it would fail, but it did not, and we were able to keep on operating until the new wheel was cast.

Kept the Mill Going

Early in the history of the Hawkesbury mill, about 1902 or 1903, we had another incident what required prompt action. This too turned out to be successful. The water in the Ottawa River from which we derived our supply had gone down to such a level that practically none was coming into the channel which we had dug from the river to the mill. So on one very hot day when it was apparent that within 24 hours we should be shut down unless the supply were augmented, I got some of the men together and we made a wooden sluice within the channel at the point where the water was still a couple of feet deep. We put a sharp incline of planks above and beyond that sort of dam. Then I constructed a little paddle wheel somewhat like the paddle wheels on the back of a Mississippi steamboat, and connected it with a little donkey engine which I brought to the spot. On this job too we worked for two days and two nights, but when the paddle wheel operated it forced the water up to a level which kept the mill supplied and we did not have to shut down. Such incidents as the foregoing might be culled by the dozen from Mr. Charles Riordon’s rich experiences. In the fields of journalism, politics, railway construction and the general industrial upbuilding of Canada he had as many experiences as would suffice for three or four ordinary men’s lives. Not the least of the things which he accomplished was to lay a foundation of knowledge of the classics, general history, philosophy, comparative religion and poetry which would do credit to many a university professor. These treasures he stored principally as the result of his unfailing habit to sit down for an hour or so in the library no matter what the time at which he reached home from the mill. He never regarded this as a task but as relaxation and recreation. Similarly he had a habit of keeping two or three books ‘on the go’ in his restless yet thoroughly concentrated mental activity. These books would lie open on tables in various parts of the house and as his active mind caused him to walk somewhere else within the house. He had a maxim that ‘the only reading which a man ever does is that for which he has no time’ might well be taken to heart by us of the present day.

Pulp and Paper Magazine February 11th, 1932

Having been born in the town Mr Riorden built it is most interesting & informative to. Read his family history. While this was greatI would like to see more on how he came to select Long Sault for his Kipawa mill later Temiscoaming

The Lumsden mill he bought some 2 miles up Gorden creek was managed by my wife’s grand father,

John Fleury. Married in Mattawa May 5, 1897, to Elizabeth Boutillette ,he was recruited by John Lumsden to move his family there & did so in 1900. His second daughter Winifred was the first child to be born in the area. A hand car was used to go by train track to amattawa to fee have & bring a doctor .

The Riodons gave mr Fleury the honour of “turning the first sod for the new mill.

Thank you Jim, for the fascinating background. We do not have any information ourselves on why he chose the area. A lot of our RPC documents were donated to the Welland Canal Museum in St Catherines. Perhaps a good place to start?